Transparent migration of web and mail services

no password resets, no downtime, no user pain

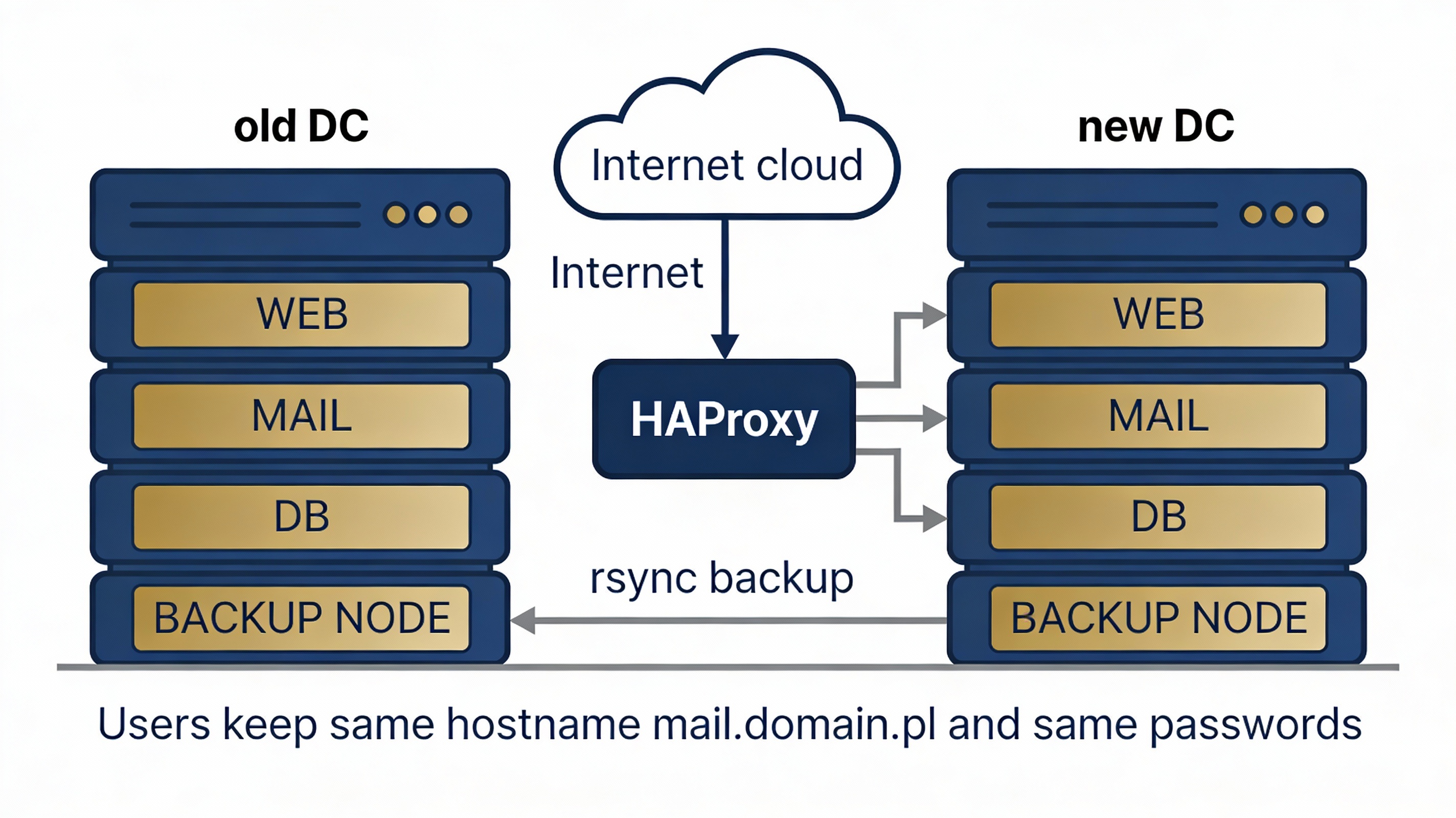

(with HAProxy, backup node and DC expansion on the way)

Infrastructure migration should not be an event for end users. If people start calling because “something has changed”, it means something went wrong.

This case describes a real‑world migration of web and mail services between servers and locations, performed without password resets, without service interruptions and without notifying users – and at the same time combined with a DC upgrade:

- adding a backup node,

- centralising backups,

- placing HAProxy as the single point of entry.

No theory. No “best practices from vendor slides”. Just things that actually worked – plus a few that broke along the way and taught us a lesson.

Assumptions – what HAD to succeed

The hard constraints at the start were:

- Users do not change passwords and do not re‑enter them – we do not know their passwords and do not want to.

- No downtime – web and mail must work throughout the entire migration.

- Migration is carried out during business hours.

- The new infrastructure must offer more than the old one – not just “the same, elsewhere”.

- We are not just “moving a server”, we are:

- adding a backup node,

- cleaning up and centralising backups,

- putting HAProxy in front as the main entry point.

Post‑migration architecture (in short)

HAProxy – single point of entry (WWW + SMTP/IMAP/POP3).

WEB server – website hosting + central database backups.

MAIL server – email service.

Backup node 1 – standby node + restore of selected data.

Backup node 2 – standby node + restore of selected data.

Users still use the same passwords, the same mail.domain.pl hostname,

and see the same website.

The only difference is on our side.

The project and milestones – how we did it without anyone noticing

Step 1: Web – why WordPress had to go

Log analysis was brutally clear: about 90% of traffic was bots, crawlers and attacks on WordPress (wp-login.php, xmlrpc.php, random *.php – every single day). The site did not need a CMS or a database – it needed to sell contact, not plugins.

Decision: WordPress OUT. Simple PHP + HTML, no SQL, no uploads, minimal attack surface. Result: CPU and RAM usage dropped, logs calmed down, most attacks stopped making sense. This was the first step towards transparent migration – the website stopped being a problem.

Step 2: Database backups – a single source of truth

Backups are created once and then distributed where needed. On the web server we generate a full dump of all databases plus a separate dump of selected application databases (WWW). Why separately?

Because servers have different roles and different MariaDB versions – you must not restore system tables onto another version. In the end, one prepared backup directory equals one file and one rsync distribution to the rest of the estate.

Step 3: Selective restore – not everything, not everywhere

A key moment: on Oracle Linux a full restore worked fine. On Ubuntu 22.04,

where MariaDB was 10.6 and the backup came from 10.5, restoring system tables

broke the business application – missing columns in mail_domain,

errors like Unknown column 'local_delivery'.

Conclusion: backup ≠ restore. Restore has to match the server’s role. Our solution: on the backup node we restore only application databases; system databases (mysql, performance_schema, sys) remain untouched. That closed the database chapter.

Step 4: Mail migration without password resets

This was the most critical part. Assumption: we do not know the passwords, we do not change them, and users must not notice anything. Same application version, same OS, same Maildir format, same mail stack.

On the new server we prepared mailboxes and migrated /var/vmail

with rsync using --numeric-ids -Aax.

We moved the mail application database with users and changed DNS.

Result: passwords stayed, folders stayed, mail clients continued working

as if nothing had happened.

The only hiccup? Fail2ban blocking rsync. Classic. Unblocked – and we moved on.

Step 5: SSL certificates – where TLS really terminates

After the DNS cutover, mail clients started complaining about an “untrusted certificate”.

The reason was simple: TLS does not terminate where the mail daemon runs,

but where DNS points (e.g. mail.domain.pl), and in our design

that was HAProxy.

In practice this meant:

- generating the certificate on the front node,

- distributing it (rsync) to the mail server,

- keeping certificates consistent across all TLS termination points.

Yes – rsyncing certificates. Yes – acceptable. Yes – it works.

Final outcome

For users:

- no password changes,

- no client reconfiguration,

- no downtime.

For the administrator:

- a backup node in place,

- HAProxy as a single, controlled entry point,

- structured, centralised backups,

- the ability to perform selective restores tailored to each server’s role.

And most importantly – the migration was transparent. This is the only migration that truly deserves to be called successful. Not every migration is a simple lift & shift. Backup and restore are two different problems. Mail can be migrated without password resets. The certificate lives where TLS terminates, not where the service binary runs. If your users did not notice anything – you won.